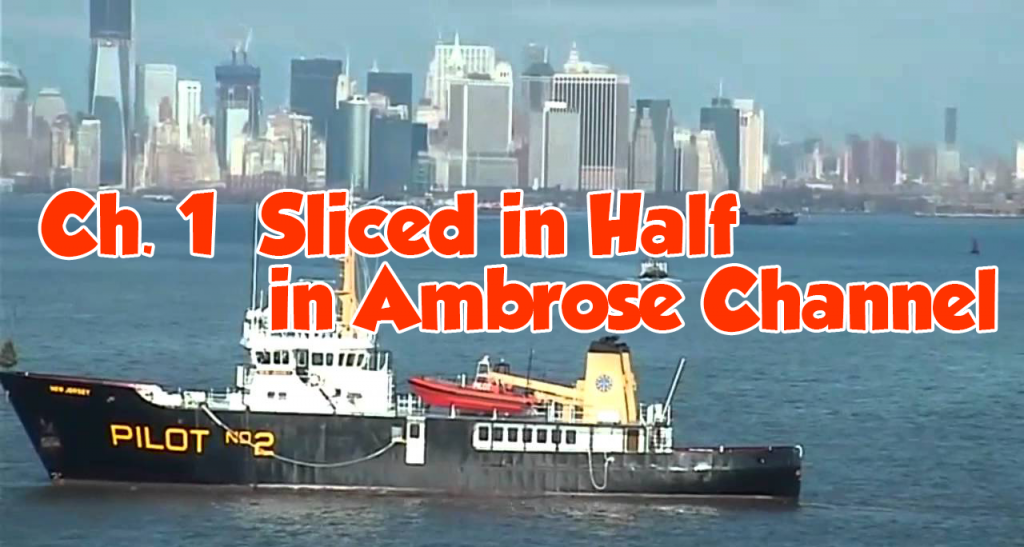

In 1914, the Marconi radio company sent Quinby out on his first full-time assignment as a radio operator, on the little pilot boat New Jersey. Just three days at sea, the vessel was T-boned in the fog off New York City by the Danish-built fruit steamer Manchioneal. (United Fruit Company, which owned the banana boat, had a huge, sophisticated radio network, but that didn’t seem to help its ships deal with fog.) The impact almost sliced New Jersey in half, and it sank in less than three minutes.

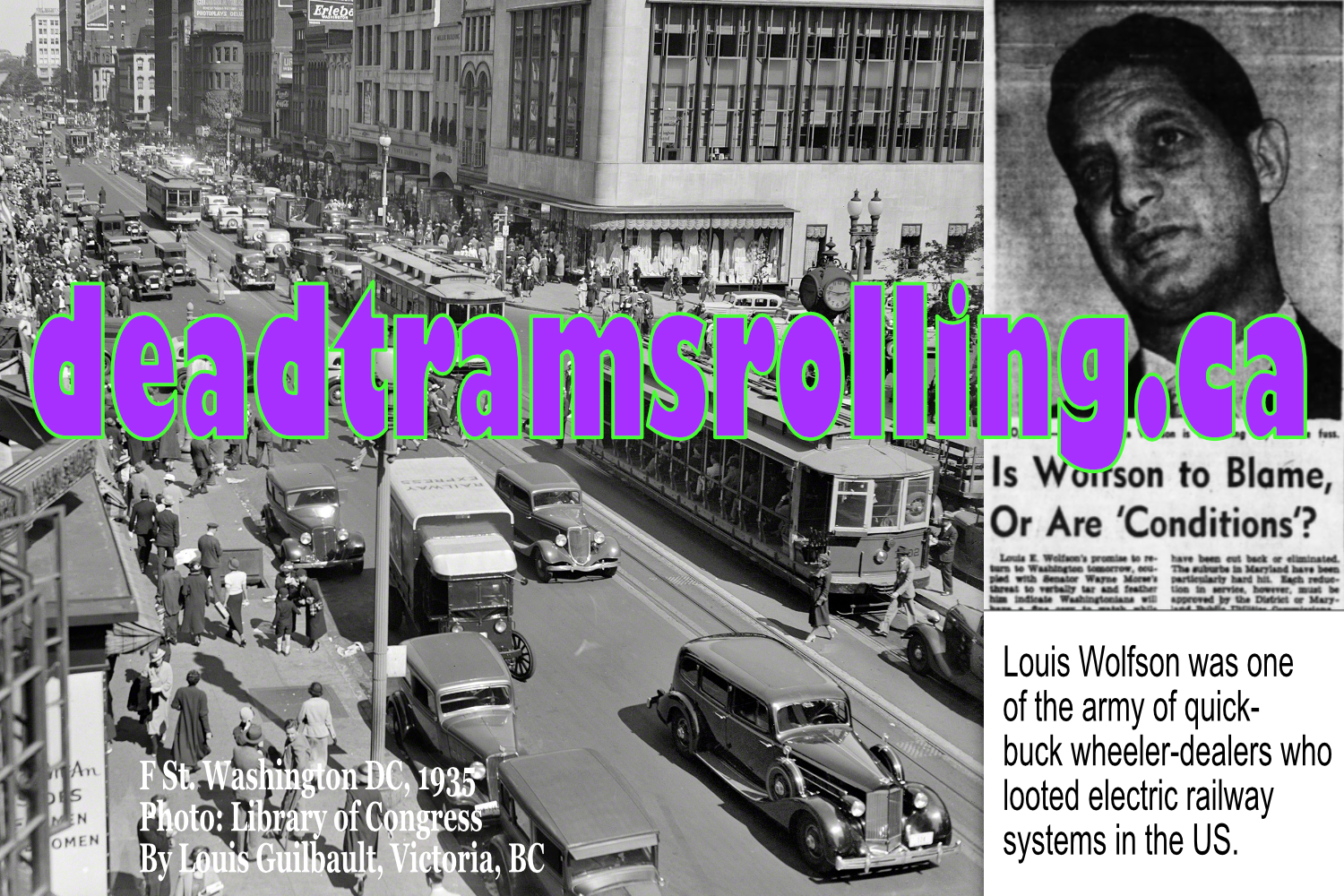

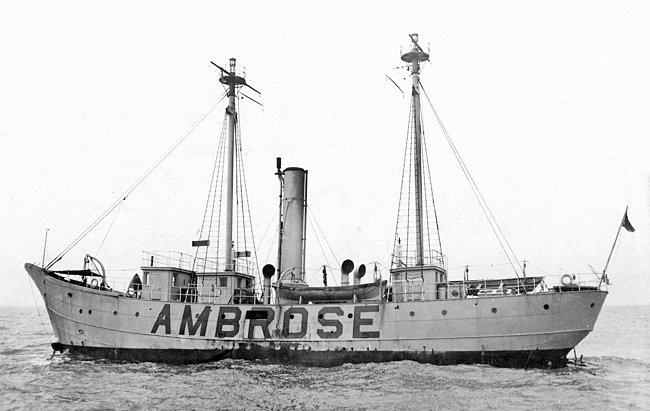

Above, Ambrose Channel, which leads into the Ports of New York and New Jersey, is one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world. This light and radio ship (LV-87) served there between 1908 & 1932. L, the ship as a museum in Manhattan today. R, pilot boats New York and New Jersey.

Jay sent out a panicked SOS and position report, but his radio room was flooded with salt water, “…sending up a choking stench from my inundated storage batteries.”

Time to abandon ship, duh, but the door to Quinby’s radio room was jammed shut. Good thing for him, he was “of slender build” (that is, skinny as a noodle.) He was able to wiggle headfirst through a porthole. All the crew made it to the lifeboat, except for Jay and the more rotund captain. Quickly, though, the two left-out crew members were able to swim to safety with the rest of the sailors.

The men on the lifeboat realized that Manchioneal was sounding her whistle in the thick blanket of gray mist, looking for survivors, but they weren’t able to connect.

Tony Tamborino, the wireless operator at Sea Gate (WSE), Coney Island was paying attention. He caught the one frenetic signal Jay was able to get off, and contacted Brooklyn Naval Yard. The Coast Guard cutter Navesink set out to look for the forlorn crew bobbing around, crossing their fingers not to get run down again. By late morning, the fog had burned off, and it wasn’t Navesink that spotted the lifeboat, but another vessel, the Raritan. The relieved sailors climbed up Raritan’s rope ladder, enjoyed lunch, and were set ashore in Brooklyn.

Quinby had to walk over Brooklyn Bridge to the Marconi office in Manhattan, what with his money and clothes being at the bottom of the Atlantic. Jack Duffy, the sympathetic manager at the office, gave dried-out “Sparks” a dollar, and sent him off to Staten Island. As the crew on Jay’s new pilot boat, New York, were having dinner, they set out for roughly the same spot New Jersey sunk.

How did a shipboard radio work in the early days?:

…the primitive wireless transmitter made a racket that could be heard all over the ship. Spectacular flashes of blue fire from [the] open spark gap and violet corona discharges from copper-coated glass Leyden jar condensers [aka capacitors] created an impressive display. Lighninglike crashes of dots and dashes never failed to attract curious passengers to the door of the wireless shack, usually left open to ventilate the heavy odor of ozone, and to publicize that the wireless equipment stood ready to serve.