Pillaging Electric Railways in Illinois & Wisconsin

(continued from home page)

The losers: Average schmuck shareholders and commuters in Illinois and Wisconsin

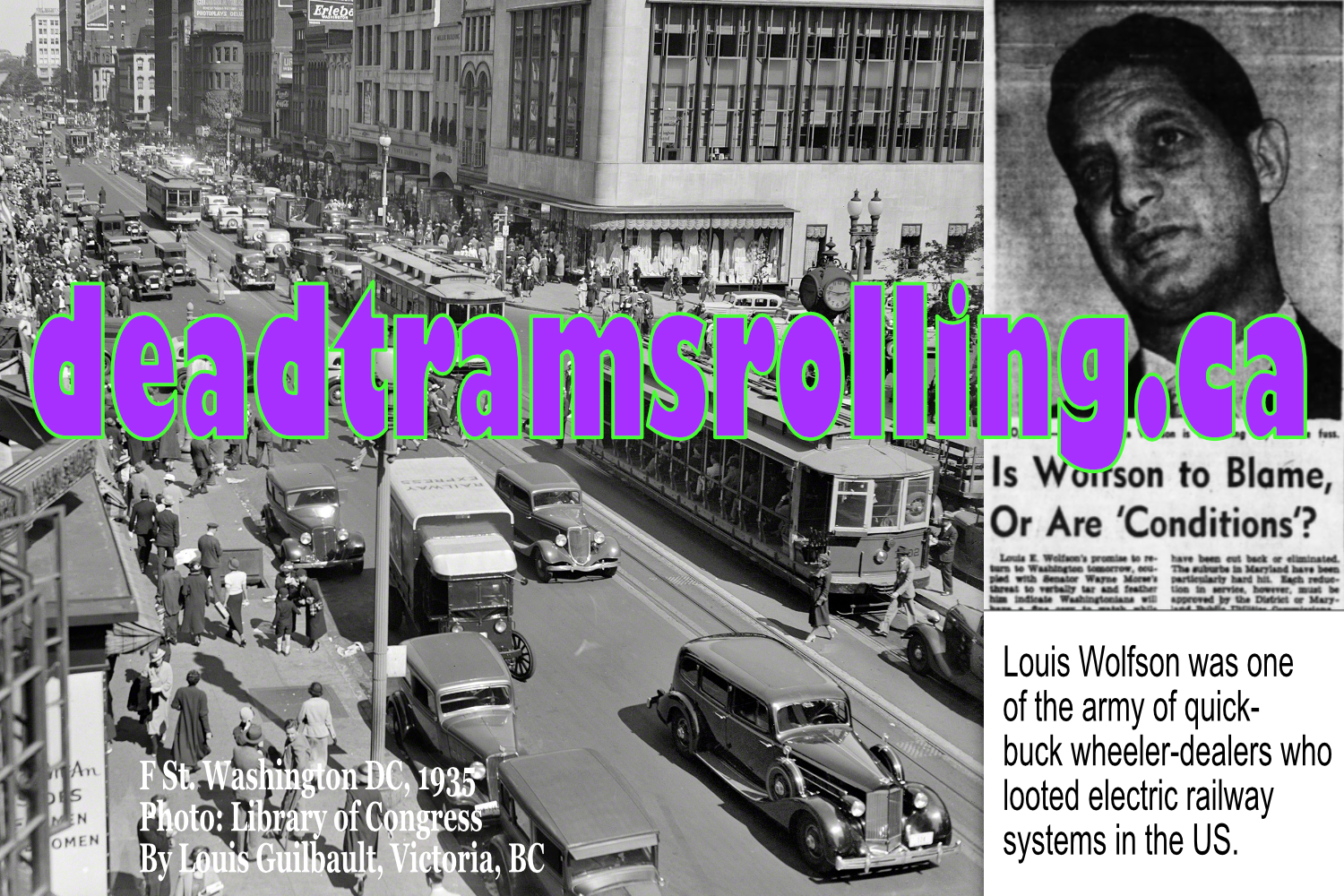

Roy Crummer, a former bond and securities dealer retired to Reno, Nevada sued Glenn Traer, Roy Fitzgerald and others in a lawsuit, Swanson v Traer, in 1950. By 1946, Crummer had owned or controlled 100,000 common shares of the North Shore. The action was against nineteen people and three corporations to recover $1.2 million from North Shore executives and their friends: money that, according to Crummer, rightfully belonged to ordinary shareholders like him.

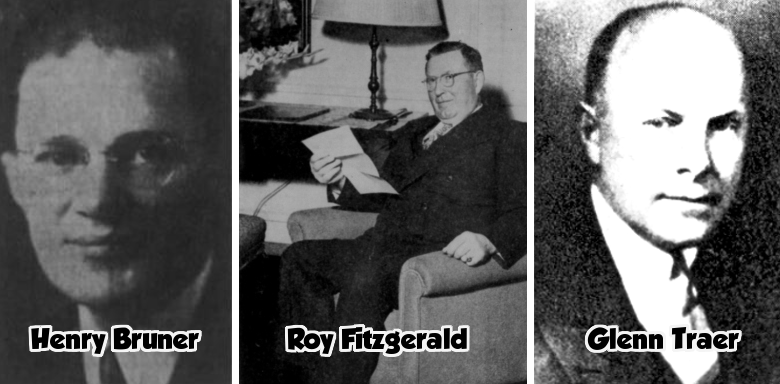

The Big Guns took their sides. Phillip La Follette was a former two-term governor of Wisconsin, and son of senator and former governor “Fighting Bob” La Follette. He and two other attorneys acted on behalf of NSL shareholders. On the other side, the three principal defendants (at least as far as this story is concerned) were Henry Bruner, Roy Fitzgerald and Glenn Traer. (Bruner was not named in Swanson v Traer, but was deeply involved in everything, and appears extensively in court transcripts.)

Traer and Fitzgerald went back a-ways. They had worked together since 1925. It was Traer who had suggested to Roy and his brothers back in 1937 that they should expand to the west coast. Traer put together the deal where Greyhound provided $150,000 so the Fitzgerald brothers could buy some Southern Pacific tram companies in San Jose, Stockton and Fresno, California. All of these were quickly converted to buses.

Amidst all this tangle of front companies, flipping assets and stock shuffling, the losers weren’t just North Shore or Transport Company shareholders. A word that appears over and over again in the legal proceedings is “salvage”—the scrap value of rails, copper wire and especially real estate. This was a huge incentive for Bruner, Traer, Fitzgerald and other vultures to keep buying electric railways.

Starting in October 1947, for example, the Chicago Transit Authority scrapped 727 streetcars and made $392,745. Each car contained an average of twelve-and-a-half tons of different grades of steel and a ton of copper and brass.

Two other noteworthy people who was part of the new NSL shareholders’ club were Greyhound executives RAL Bogan and Manferd Burleigh. Greyhound and National City Lines both traced their roots to northern Minnesota. They were close pals and frequent business partners. With this bunch running the railroad, one thing was 100% certain: no more Electroliners. In fact, 1941 was essentially RIP for the whole American electric railway manufacturing industry, except for a few subways. From that year on, and to this day, the innovation would come out of Europe and Asia.

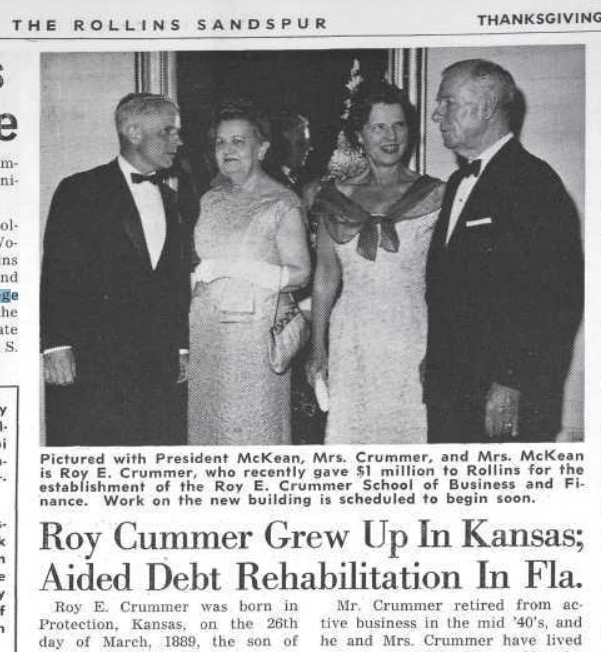

Phillip LaFollette, former two-term Wisconsin governor, launched the Swanson v Traer suit along with two other lawyers, on behalf of large NSL shareholder Roy Crummer. Below is Roy Crummer after making a million-dollar donation to the business school at Rollins College in Orlando.

Henry Bruner Enters the Picture

Besides Traer and his NCL gang, somebody else was picking the bones of electric railways clean: utility executive turned transit “consultant” and all-round wheeler-dealer Henry Bruner. (Bruner had also, no surprise, been pals with Fitzgerald and Traer since before 1939.) Bruner was a Harvard business school graduate who knew a lucrative racket when he saw it; he was ace at leveraging something from nothing. The Swanson v Traer trial record gives a slew of fascinating detail about the plunder of both the NSL and Milwaukee Transport Company:

In seven years, starting at the age of 39 with personal assets of only $16,000 ($307,000 in 2021 dollars). Bruner bought “distressed” interurban lines from the Transport Company of Milwaukee, which provided local transit surface as well. Like Fitzgerald and Traer, Bruner picked up these rail lines for a small fraction of their original values. The Transport Company benefited from tax savings for writing off the assets,.

A great way for Bruner to get rich in a hurry was to pay himself a bunch of different salaries, including $25,000 ($38o,000 in 2021 dollars) for running Shore Line Transit, $15,000 ($231,000) for managing Racine Motor Coach Lines (plus another six hundred bucks ($9,200) for his wife), $7,500 ($136,000) for the Appleton and Intercity Bus Lines and $10,000 ($154,000) for being boss of Kenosha Motor Coach Lines. Grand total: ($910,200). Ka-ching.

EM Goodman, a Milwaukee lawyer, filed another suit than Swanson v Traer against Bruner for much the same reasons as in the bigger case. Goodman called Bruner a stooge and said the bus company sales were fraudulent, but the judge disagreed.

Like many interurbans (and indeed like many companies and tens of millions of people), the North Shore fell on hard times in the Depression. Fitzgerald and his pals said their goal buying NSL shares was to put the company on a sound financial basis and “physically rehabilitate and modernize” the service. Judging by how NCL usually operated, this translated into ripping out rails, selling off assets and buying General Motors buses. In 1947, naturally, NSL got rid of local streetcars in Waukegan and North Chicago, bought twenty buses, and jacked fares up from seven to ten cents. In 1948, NSL scrapped the original rail line that ran right along Lake Michigan, and converted it to buses as well (the inland Skokie Valley rail line was retained.)

It’s not clear whether it was Bruner or Traer and Fitzgerald who created Shore Line Transit, in May of 1945. What is clear is that, after putting up only $60,000, Bruner sold his bus companies to Shore Line for $595,000. Then Shore Line sold the same companies back to to NSL for $1,682, 835.67. A sweet deal indeed for Bruner! (it also cleaned out about half of the railroad’s cash reserves.) In 1948, Shore Line Transit, whose main purpose seems to have been fattening the bank accounts of Bruner, Traer and Fitzgerald, was dissolved. It had served its purpose admirably.

Roy Crummer wasn’t consulted about any of these dealings, even though he owned a big chunk of NSL stock. Nor were many of the company directors. In fact, Crummer thought the whole idea of the train company going into the bus business was “completely unsound.”

The final Illinois Appeals Court appeal of the North Shore legal action was decided in February of 1956, after more than five-and-a-half years of litigation. The judge ruled that the railroad had not fallen into “antagonistic hands”, as the prosecution argued.

The case was then appealed to the US Supreme Court. The judges in Washington DC in a 5-4 decision, overturned the Appeals Court decision, and said that Traer and others had indeed acted in a way that was antagonistic for shareholders. The verdict was given by Justice William O Douglas in June of 1957.

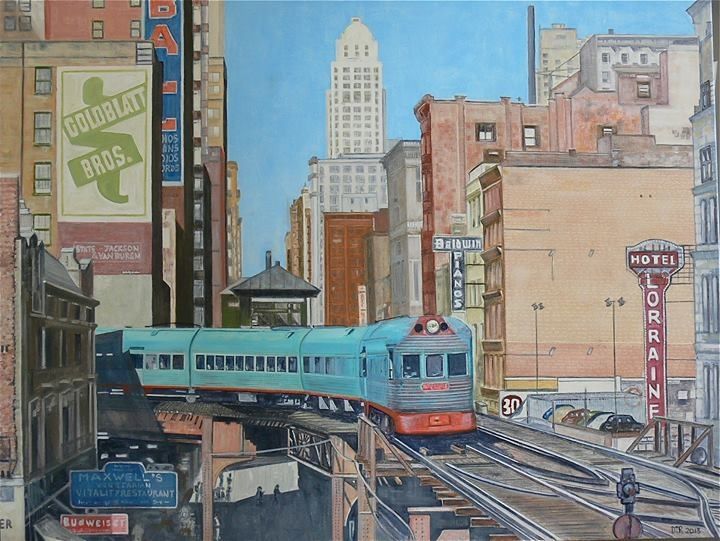

Electroliner Workhorses, 1941-1978

The sleek, turquoise and orange passenger trains (with lightning-bolt accents!) turned out to be more than pretty faces: they ran faithfully between Chicago and Milwaukee ten times a day for 22 years, when NSL folded in 1963.

Then the trains were repainted red and white, equipped with third-rail power instead of overhead catenary, and shipped off to Philly, for commuter service to the northwest suburb of Norristown. They were renamed Liberty Liners, and operated another fifteen years.

By 1978, when the Liberty Liners finally retired, Japan had charged ahead with high-speed trains, and France was three years away from opening its first TGV line. These two Electro/Liberty Liners are a vivid reminder of what America could accomplish, and that the country had not always been a blando mash of freeways and parking lots.

Different Story for the South Shore

The Chicago, South Shore and South Bend interurban runs from Chicago across northern Indiana. It is the only interurban in North America that has survived to the present day.

The North Shore and South Shore shared one honor in different years: they were both recipients of the annual Charles A Coffin medal awarded to innovative electric railways. This prize, named after the General Electric president and cofounder, was a big deal for electric railway companies, rather like winning a Nobel for a scientist or an Oscar for somebody in the movie biz. The South Shore picked up the award in 1929 after utility tycoon Samuel Insull laid out thirteen million dollars ($208 million) for upgraded track and new trains and stations.

The improvements slashed the travel time from Chicago to South Bend from three to two hours; these resulted in monthly ridership leaping to a quarter million, and monthly freight tonnage growing to 250,000.

In 1976, the South Shore was caught in the familiar vice of aging equipment and declining ridership, and applied to abandon the service. Instead, the state of Indiana came up with annual grants to allow the railway to run and improve service. The state later took over direct control.

Today, all of the South Shore’s trains were built by the Japanese Nippon Sharyo company, because of course there is no American company that could do it. The line carried a very modest 4,600 weekday riders.

However, in 2024 the South Shore opened a $650 million upgrade to its line. The service is now completely double -tracked, travel times are slashed, and 53 trains per day will operate on weekdays. Ridership will likely improve substantially, though it’s too soon to provide numbers.

Above, Indiana’s Republican governor Eric Holcomb wields the giant scissors for the South Shore improvement project, while Democratic Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, to Holcomb’s left, watches proceedings. Below L is Supreme Court justice William Douglas, who ruled for the majority in favor of Roy Crummer in Swanson v Traer in 1957. R an Electroliner painting by David Reilly in Chicago.