The passenger liner Susquehanna (KOLN) set sail from New York harbor in August 4, 1920.

Party time! since this was the rebirth of the US merchant marine. Long strings of bright flags fluttered from the the liner’s rigging. Small boats tooted. Newsreel cameras clattered, as a fireboat produced long streams of water. Overhead, a plane buzzed.

Sparks was chief radio operator, his assistant Jack O’Connell. This was a class operation, unlike the disheveled, borderline bunch on the Ida. Quinby and O’Connell were decked out with complete sets of winter and summer uniforms at S Appel tailors on lower Manhattan. The big liner had two missions, one being to bring some of Europe’s war refugees to America. She was also delivering a big load of coffins (?) to Warsaw.

After a rough Atlantic crossing, Susquehanna passed Dungeness, at the entrance to the Straight of Dover between France and England. The UK radio operator asked if Captain Dundas wanted to take on a North Sea pilot. The American captain said no thanks, since it was open sea till the German port of Bremerhaven. What Dundas did not know was that there were still German minefields that hadn’t been cleared. He set a course right through one of them! The gods smiled, and the ship passed through unscathed.

The American liner had been built as the Rhein for the German Lloyd Line in Hamburg in 1899, then seized by the US Navy to get 15,537 troops home after WWI. As it proceeded through Kiel Canal, (which allows ships to access the Baltic Sea without detouring around Denmark) German guards were disgusted to see the Stars and Stripes flapping on the vessel. “HOCH! (hell)” a group of them yelled as it exited the 61-mile canal. Disciplined soldiers, they saluted reluctantly instead of raising middle fingers (Latin: digitus impudicus. Ancient Greeks “used the middle finger as an explicit reference to the male genitalia.”)

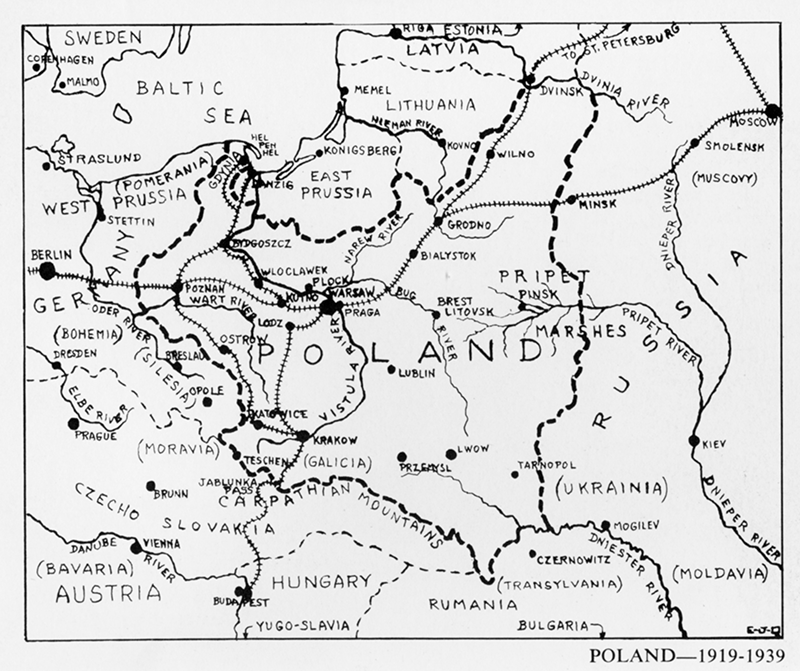

They tied up in Danzig, now called Gdansk, in Poland. This city at the mouth of the Vistula River had been mostly occupied by Prussia for previous centuries, but was set up as a semi-independent “free state” under the terms of the WWI Armistice to give Poland a seaport.

A lot of people on the dock seemed especially eager to get the coffins on a train, one of them a beautiful blond woman named Victoria Fens. Sparks was introduced to the mysterious Fens, and Captain Dundas asked him and O’Connell if they wanted to take a trip to Warsaw.

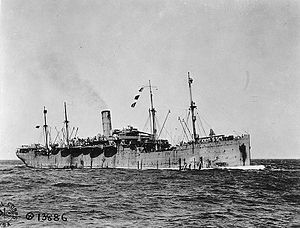

L, Susquehanna before its maiden voyage with Quinby. R, while serving as a troop transport in WWI.

At two the next morning, Jay ‘n’ Jack were roused out of bed and handed fake credentials and wads of Polish money. They transferred from Susquehanna to the waiting train. The whistle on the steam locomotive blasted, and they were off through another land in turmoil. Shortly after setting out, the train was stopped, and everyone ordered outside to show their papers to a heel-clicking German officer. The two Americans had been recruited because Germans were contemptuous of anything Polish, but respectful to the USA.

At the crossroads city of Bydgoszcz (pronunciation? you’re on your own) the train stopped abruptly. The direct line to Warsaw via Kutno had been seized by the Bolsheviks, who were trying to take over the country.

A Polish officer was stuck in Bydgoszcz with a train full of soldiers, but no locomotive to pull it to Warsaw. His plan was to commandeer the power unit on Victoria’s train. Fens wanted Jay to assert his authority, though in fact Quinby was just a schlep civilian radio operator. Bluff was everything.

After some intense discussion, the train engineer suggested coupling the two trains together. This was a great idea, except that the much heavier train was a bitch for one locomotive to pull. As a crowd waved and cheered, the engineer set out on a wild ride, going like stink on the down-grades to make it over the up-slopes.

At ten next morning, the train had veered far to the southwest, to Poznan. This was a helluva roundabout route to Warsaw, a detour of around 1,000 versts (a verst being 500 sazhen. Does that help? No? Well, a verst is archaic Russian measure of length, about 0.66 mile (1.1 km)) , or 600 miles. (Think of traveling from Chicago to New York via New Orleans.)

At the railway yard in Poznan, the Polish fighters and two token Americans had to come up with another locomotive, since the circuitous route to Warsaw was mountainous. Everyone went to the dispatcher’s office. After another bout of heated debate, a bigger power unit was added to the one that had gotten them as far as they were.

A new train crew came aboard, they filled up with coal and water, and set south for Ostrow. Armed sentries were posted on roofs of the rail cars to watch for Bolshies. Again there were crowds of peasants cheering the train onward.

The train had to head far south to Katowice, near the Czech city of Ostrava, then to the ancient capital of Krakow. There, after traveling southeast for hundreds of miles, they set off in almost the opposite direction, north-north west to Lodz. Finally, with eyes hurting from Polish scenery overload, they rolled east into Warsaw. The coffins were unloaded, most of which were of course packed with rifles and ammunition. J&J could hear the rumble of war, not far to the east.

The Americans were put up at the Dom Oficiera Polskiego, the Polish officers club. That evening, “There was no running out of ideas for toasts, no running out of vodka.”

Next morning, though J&J’s heads throbbed, the news was terrific: the Reds were in retreat. The Americans headed directly back to Danzig on the first train to use the route since the Bolsheviks had blocked it.

Back on the Baltic port, thousands of detainees were holed up in a primitive detention camp, the displaced from what then was the biggest war in history. Some of the camp dwellers were so emaciated they could barely stand. Doctors and nurses worked non-stop to provide treatment.

Gradually some war victims were processed and made their way up the Susquehanna’s gangplank. As some set foot on the ship, they kissed its deck. Fortunately the liner had a huge, well-stocked galley. Head chef Shorty Schwartz saw it as a professional challenge to get tasty and solid food into the passengers’ bellies.

In 1922, Sparks took a land job, at RCA labs in uptown Manhattan. There, he came up with several patents for the company, and founded and edited Broadcast News magazine. Four years later, a bit younger guy in Kentucky set out with a pal on his own South American journey.

L is six-foot Quinby, center head chef Shorty Schwartz and R the seven-foot ship’s chief steward on Susquehanna’s deck.