Captain Magee struggled with discipline the entire voyage. The chief engineer, first assistant engineer and third mate drank and partied with the crew and defied orders. February 14, 1920, Valentines Day, was the chief engineer’s birthday (it was also the date when, nine years later, seven gang members would be gunned down against a garage wall in Chicago.) On Ida, most of the officers and crew got blotto. Then they used the excuse of crossing the International Date Line to do it again.

The situation onboard slid to a similar nadir as what they had fled in Russia: chaos. The firemen who were supposed to keep the boilers going joined the drinking and carousing. The engine barely turned over, and the ex-Austrian tub bobbed helplessly in the not-at-all Pacific.

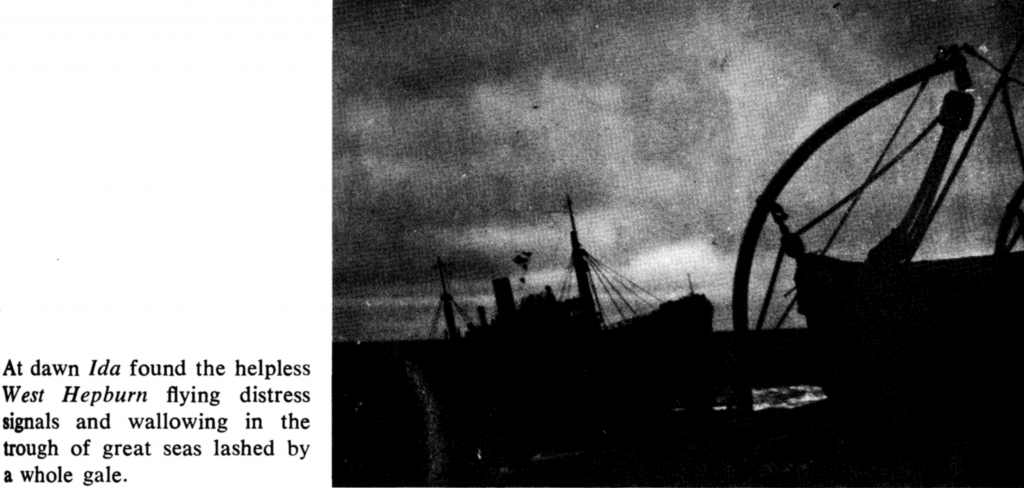

Quinby thought they could need help, so started dialing his radio to find out who was out there. Then he heard a desperate distress call: SOS SOS KDKN KDKN. KDKN, Jay discovered, was a US ship, West Hepburn. She had lost her propeller and was taking on water. Jay wrapped a message to Magee around a bar of soap, and slipped it down a ventilation shaft to the captain’s quarters. He didn’t want a drunken confrontation with his belligerent crewmates.

Soon afterwards, Sparks heard a knock at the door. He was shocked to see not just the captain, but the chief engineer and first mate, standing outside.

It was this fortunate emergency that broke the evil spell of Ida’s mutiny… Everybody sobered up and the crew worked feverishly to charge toward West Hepburn’s position, roughly south of the Islands of Four Mountains in the Aleutians (52°N, 170°W) and again at about the same latitude as Vladik (43°N), north of San Francisco (38°N.) For perspective (values rounded) Portland OR is at (45°N), Tokyo (36°N) and Seoul (41°N.)

Another freighter, the Osaka Maru, also heard West Hepburn’s SOS, but the disabled US ship radioed that Ida’s signals were stronger than those of the Japanese vessel.

Pre-radar, pre-GPS, it wasn’t easy finding a ship on the stormy, nearly sixty-four million square mile expanse of Pacific Ocean. Magee told the helpless US vessel to sweep the horizon with her searchlight. The radio signal was strong, but nobody on Ida could glimpse the ship. Sparks suggested setting a perpendicular course to see if the signal grew weaker or stronger. Sure enough, after an hour, the radio signal faded, so Jay’s ship turned around.

Magee came to Jay’s cabin and sent a message to have West Hepburn point its searchlight at the clouds. Sure enough, the bridge finally spotted the reflection. The rescue ship sailed directly to the source of the light.

The seas were running so high that one moment we looked up at her [the West Hepburn] as she rose on the crest of a wave, and we slid down into a trough. The next moment we found ourselves peering down at her as she plunged into a watery valley and Ida climbed an adjacent peak.

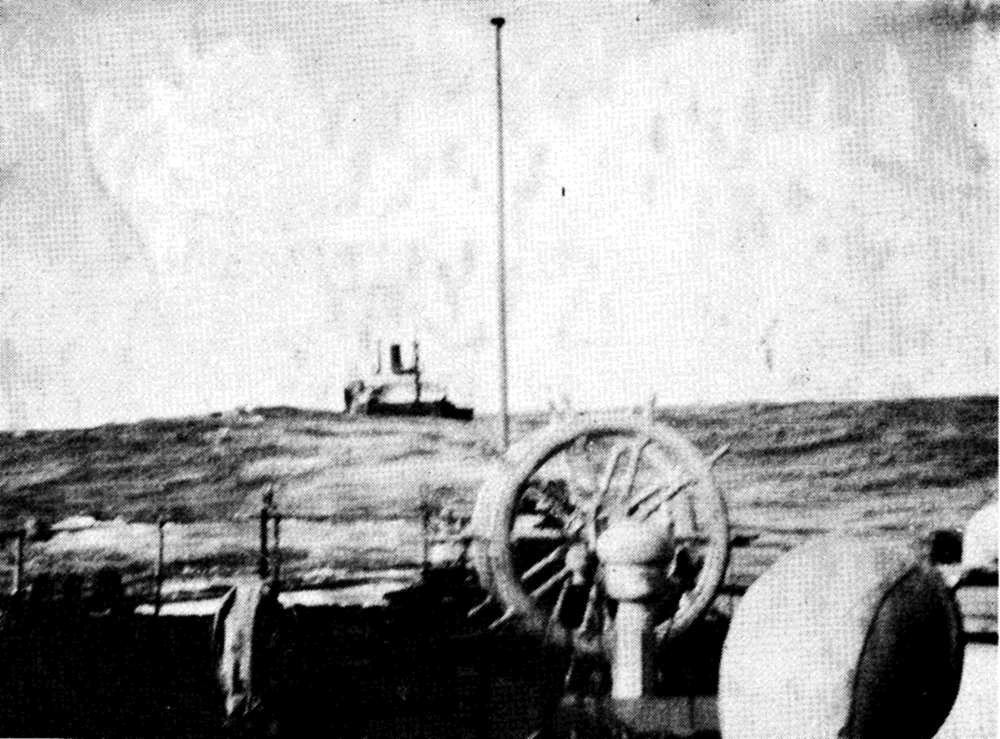

Ida’s captain had to perform some endless, delicate maneuvering in circles to close in, but not to get so near as for the two vessels to crash together. On the third try, with a twirl of the line like a rodeo cowboy, the Dutch bosun heaved a weighted line onto West Hepburn’s deck. Two sailors on the stricken vessel pounced on it as the crews on both vessels cheered raucously.

While Magee’s ship performed its elaborate nautical dance, Osaka Maru appeared. It circled the scene a couple of times. Seeing things were in hand, it set out eastward.

It took several hours to get a steel cable set up between the two vessels, rigged so that there was some give to allow for the churning ocean. The pair of US ships set out for San Francisco, but then after a few hours the cable broke, sliced by the sharp edge of West Hepburn’s deck!

More hours passed getting another line to West Hepburn. This time, the disabled ship’s captain saw the advantage of using the hawse pipe (the thick, reinforced opening at the bow that the ship’s anchor chain slides through.) Quinby said of Magee’s skills:

In a lifetime of seagoing experiences in and out of the US Navy, I have never witnessed a better exhibition of expert seamanship that that of James T Magee in that raging storm which, as though to confirm the stunt was not accomplished through sheer luck, he repeated within a few hours!

Towing the big US ship was slow going, and Ida went through a lot of coal. West Hepburn was an oil burner, so its fuel was of no use. Around 145° W, the last of the Myike fuel was gone, still far west of California. Ida, though, did have something else to set on fire: a thwack of Philippine mahogany. Expensive fuel, but it beat trying to row. Nearing the Golden Gate (the bridge was 17 years in the future), even that was up in smoke. So the crew pulled off the wooden hatch covers, and any other combustible objects they could find, to heave in the maw of the boilers. They barely made to a pier without having to be towed in.

A Bay-area businessman was eager to pick up his extremely late delivery of mahogany, when captain Magee explained it had all gone up Ida’s smokestack. Infuriated, the Californian stormed off, then slapped a lien on the ship.

West Hepburn hooked up to Ida, en route to Californie.

Waiting in San Francisco were a pair of letters from the two young Russian women (another crew member, Jay’s friend Beauregard, had fallen in love with and engaged Sonya’s sister Tanya.)

Beau’s hometown was Charleston. He was Ida’s supercargo (from the Spanish sobrecargo.) His job was to manage the huge range of stuff the tramp steamer lugged around, buying and selling in the various ports of call.

Jay, Beau and the rest of the crew on Ida did the traditional thing and spruced up their tub for her return to the Big Apple. Sparks cleaned and scraped and painted his radio cabin, then went for a Bay area tour with Beau.

Returning to the ship, Jay noticed the light was on in his quarters, which was odd because he was sure he’d turned it off. Opening the door, Sparks discovered his monkey pals Mike and Maggie had gotten out of their cages and painted the town red.

White, in fact, since the furballs splattered the cabin interior and themselves with the can of white enamel they’d nimbly managed to get the lid off of.

That was just the start. It looked like Christmas with the feathers from Jay’s pillows floating around, those that weren’t stuck to the freshly painted interior surfaces. Water gushed from both taps, which drenched everything in the two drawers under the bunk. Sparks’ dog Chow was also covered in paint, and got white paw prints over everything. M&M smashed the radio tubes.

“Couldn’t you two devils think of anything else?” Quinby inquired of the two apes.

“Sk! Sk!” was all they could come up with in reply, accompanied with contorted facial expressions.

Once all the legal wrangling over the incinerated wood was worked out, Ida set south for the Panama Canal. The toxic environment on the ship returned, again fueled by alcohol.

Third Officer Shaver almost ran the ship onto Catalina Island off Los Angeles, which resulted in captain Magee ordering him off the bridge. Shaver continued hurling abuse at Magee, and the captain demoted the argumentative officer to ordinary seaman.

Then First Assistant Engineer Korman called the Russian sisters whores. This resulted in Beauregard planting a right on Korman’s jaw, knocking the mouthy sailor to the deck. Sparks was pretty irate too, but Beau pointed out that Korman was a big, nasty dude who could easily flatten the radioman.

A couple days later, a bare-fisted boxing match was set up on Ida’s deck. Korman was a bit bigger than Beauregard, but he was also older and less fit. Both men bled and grunted and flailed around. Then the younger gladiator once again landed a powerful right, and Korman went down for a second time.

Possibly the only reason things functioned at all on Ida may have been because of a higher authority: poker. Games went on for days, Hatfield/McCoy feuds forgotten. Unshaven participants guzzled coffee and puffed on pipes and cigarettes. With his math aptitude, Sparks did better than average. He wasn’t so much of a ringer, though, to be barred from participating.

When Ida’s crew went ashore in Balboa, Panama, waiting to enter the canal, Captain Magee sent a telegram to the shipping board in NYC. The cruise from Panama to New York was uneventful, and somewhere off New Jersey, Sparks radioed station WNY in Manhattan’s Bush Tower to arrange to meet a pilot.

Quinby thought the shore operator replying had a familiar “fist”, that is, his style of sending Morse code. Sure enough, when Jay asked for the New York radioman’s “sine”, he replied “RG.” Of course, his pal Ray Green.

On April 8, 1920, Ida picked up her pilot near Ambrose Lightship as dusk settled. In seven months a fundamental transformation had occurred. It was no longer just the dots and dashes of Morse code on the airwaves. Voices and music came over among all the chatter. Thrilled to hear this, Jay ran to the bridge to invite Magee to listen. The captain was as astonished as his radioman: “Thanks, Sparks. Now I’ve heard everything!”

The mutiny on Ida was investigated, and the sailors responsible tried (the civilian equivalent of a court-martial.) Three of the officers had their licenses suspended for between three and twelve months, and others were logged for pay during periods when they weren’t doing their jobs. Jay got a check for $600 for his share of rescuing West Hepburn, plus another $200 for the clothes and effects he’d lost on New Jersey.

Some of Ida’s crew members. The monkey was probably one of the decorators of Quinby’s radio room.