In October 1919 Quinby set sail on his über-eventful Pacific Rim tour on Ida, which was an ex-Austrian freighter captured by the US Navy in WWI. Bill Fitzpatrick, agent for the Marconi radio company on Manhattan, had phoned Jay and said, “You take this freighter out, and you’ll see some mighty interesting sights and have some very interesting experiences.”

This, for once, was no telemarketing con. The pay (thirty bucks a month) was lousy though. (According to the website Career Trend, the average American income in 1920 was $3,269.40.) Some sailors supplemented their incomes with trading and smuggling. On coal burners, it helped that there were all kinds of places to stash contraband in the black piles deep in the hull.

In January 1920, Prohibition, the nationwide ban on alcohol sales in the US, came into effect. Keeping alcohol under control was a huge challenge for Ida captain James Magee.

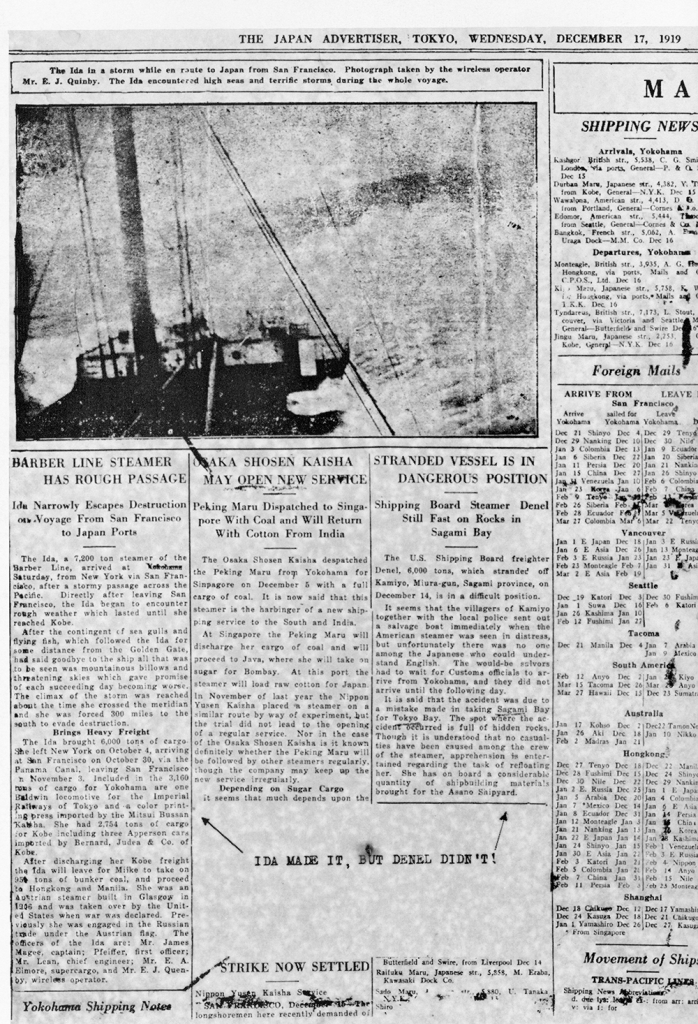

As Christmas 1919 neared, the steamer approached Yokohama after struggling through powerful northwest gales, which knocked her far off course. The ship lacked a radio compass, so establishing exact position was a challenge. In the clouds, it was impossible to use the stars to take bearings. Six to seven inches of water sloshed around in the steamer’s hold, and pumps barely kept up: “…the violent rolling and pitching caused [the engineers’] pumps to suck up more air than water, as the intakes were exposed half the time.”

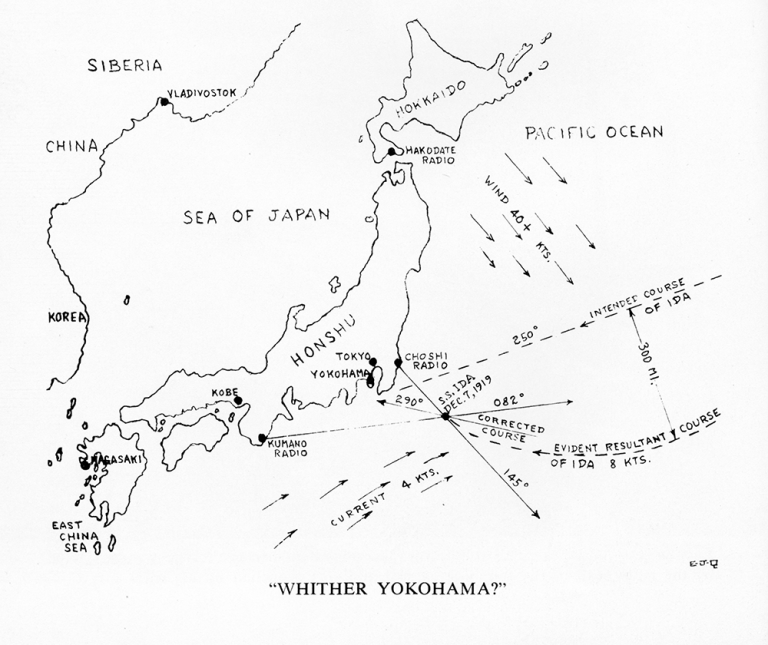

Luckily for Quinby, he was able to pick up Japanese radio stations at Choshi and Kumano. With his feeble 1/2 kW transmitter, he could only send messages at night as Ida crept towards Honshu, the biggest Japanese island. Finally, after a mixup with the Kumano operator, Quinby and and Magee were able to fix a position. The storm had shoved the ship 300 miles off course!

Above, Sparks’s map of his estimate of how far Ida was of course. Below, the newspaper stories reporting Ida’s arrival and Drenel’s sinking.

Groping his way along as slowly as possible, Magee thought he was on his way into Tokyo Bay:

Something was obviously wrong. There was no sign of habitation on the steep shores. As we eased around a point of land, we were suddenly confronted with towering hills. “Back her full,” ordered Magee, and as Ida lost her headway, the mate stood by on the fo’csle to let go the anchor if necessary. Several small fishing boats crowded close to Ida, their crews yelling excitedly in Japanese. They made gestures, holding up their fishing nets and spinning their fingers through them to indicate that our screw was tangling up their nets…they obviously understand our one word inquiry “Yokohama?”

In response and in unison, they all made sweeping gestures in wide arcs toward the east…We proceeded to leave. With the bosun heaving the lead and warning the bridge against shallows, Ida cautiously eased out of the cul-de-sac into which she had blundered.

Finally turning into the entrance to Tokyo Wan, Magee’s vessel took on the pilot, who said that the ship was extremely lucky to not have hit the rocks. Shortly after Ida’s close call, another US vessel, the Drenel, loaded with steel for the Anaso shipyard, made the same mistakes. She smacked the jagged Japanese coastline near the village of Kamiyo in Sagami Bay and was a write-off. Luckily the crew survived.