The day after Christmas, 1919, captain Magee got word that his next stop was the famous Russian Pacific port city. A Japanese radio operator, visiting Quinby when the message arrived, was incredulous. “You’re going to Vladivostok?!?” he exclaimed. “I wish you a lotta luck.”

The mid-winter weather cruising towards Siberia was foul. A trip that should’ve taken three or four days took five. Crappy conditions meant that Quinby’s feeble radio picked up only static. Smack in Ida’s path was Dagelet Island (which now goes by its Korean name of Ulleungdo.) Magee prudently made a wide detour, then proceeded due north through the Sea of Japan.

In terms of latitude, Vladivostok is slightly south of Nice, France. A huge weather system called the Siberian High, however, usually centered around distant Lake Baikal, means weather in this part of the world lurches between hot and humid summers and surprisingly cold, dry winters. This is why the aurora borealis (Northern Lights) are visible in winter in “Vladik” (and Ida’s crew witnessed a terrific display) but you won’t catch them from the balcony of your five-star Riviera hotel.

(The Northern Lights are wondrous. One ridiculously cold night in Edmonton (-30-35°C) I caught the most spectacular display of my life, standing mesmerized outside the U of A’s Dentistry/Pharmacy building (a place where a starving student could get his teeth worked on by a dental student for cheap.) In this case the lights weren’t very colorful, more giant white shafts sliding up and down in the sky. Even though my bod was bundled up well, after awhile my toes went numb, and I was forced to turn away from the free show.)

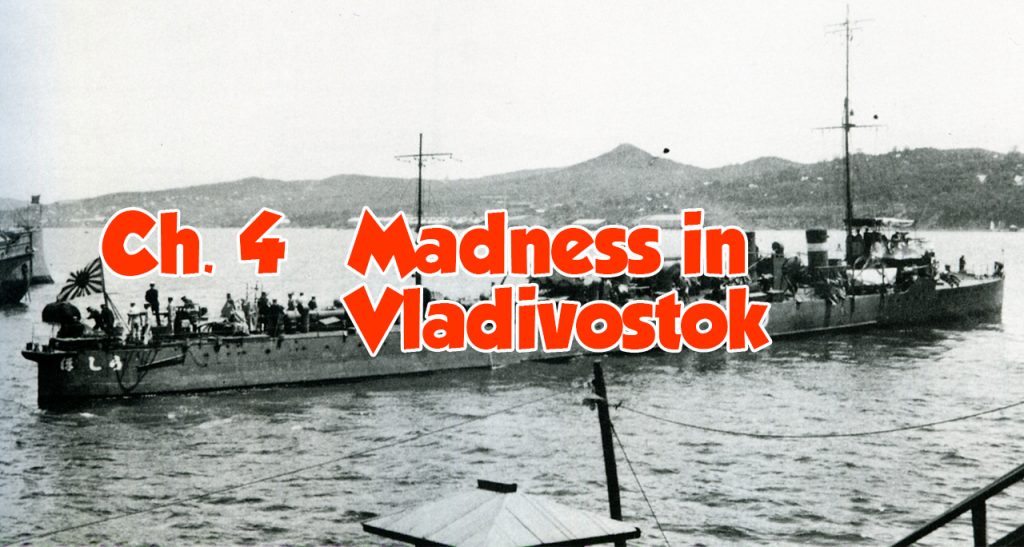

New Year’s Eve, 1919, Ida cruised obliviously into a cauldron of anarchy: post-revolutionary Russia. Why was it that the only vessel crew could glimpse in this major port was the American battle cruiser Brooklyn? Ida put out her anchor and McGee gave the command ALL FINISHED WITH ENGINES. The steamer’s chief engineer dismantled the coupling between the engine and its propeller to replace the key which finally, inopportunely, had just sheared off.

Brooklyn ran up a series of flags to warn the freighter of its dicey position, but the crew couldn’t make them out in the dusk. Crew members on the American warship were no doubt thinking, “What are these eeediots doing?”

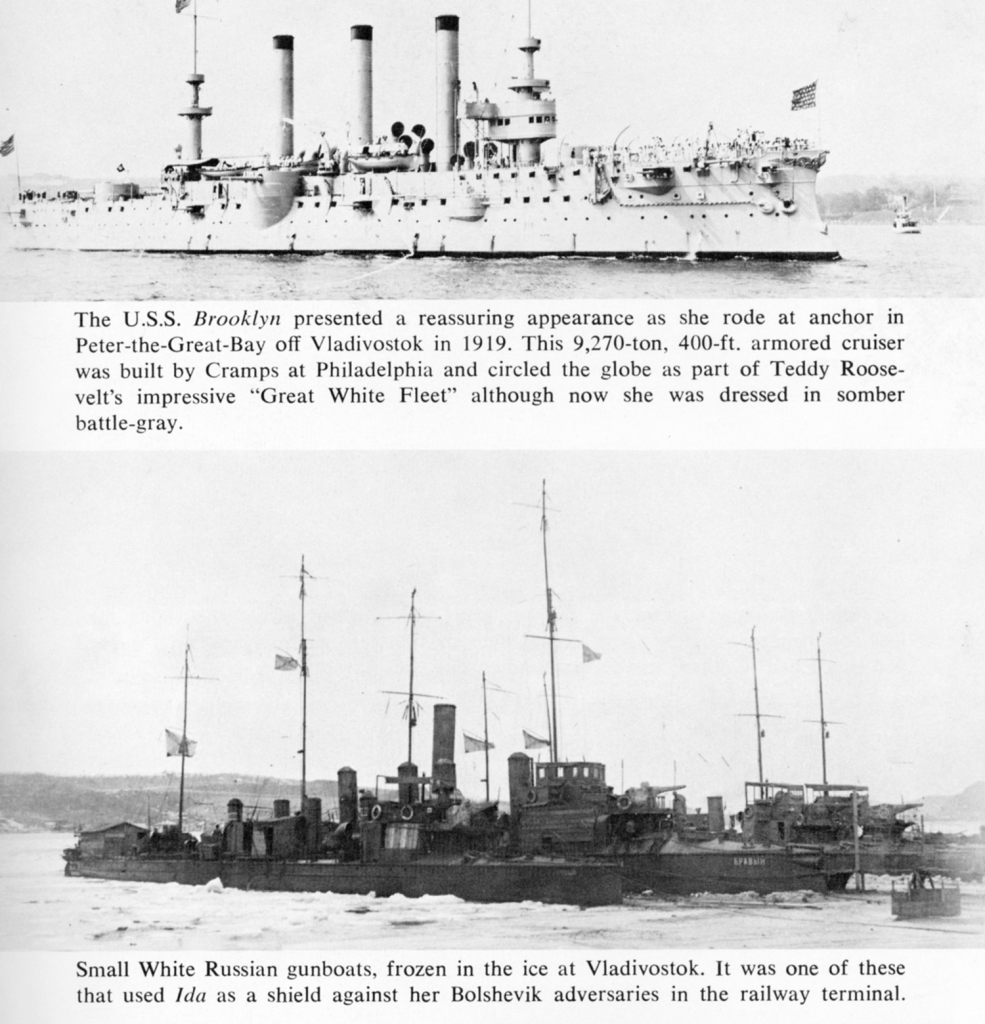

A White Russian (Imperial, pre-Communist) gunboat appeared. It was shooting, and Magee thought this was just a part of New Year’s Eve festivities. A shore battery, probably Bolshevik/Communist, fired at the gunboat, which took cover behind the new arrival.

A couple of shells punctured Ida’s smokestack. “The little gunboat was obviously taking shelter behind the new US visitor and the gunners ashore were attempting to hit her by firing through Ida’s rigging.” Only later did the crew realize their luck in that none of the bullets punctured the cargo in the hold: big tins of fuel oil.

When Brooklyn got the message that Ida was under repair and incapacitated, the US warship sent over a boat. A young US Navy Lieutenant Bailey told Magee, “…some revolutionaries have taken over the railway station and have set up some guns in there. They’ve been shooting at everything in sight for some time now.”

Terrific. But things had actually got much better for Ida when the irksome Russian gunboat, wisely, fled. American Admiral Knight transmitted the message, IF YOU DON’T GET OUT FROM BEHIND THAT AMERICAN MERCHANTMAN I’LL SINK YOU MYSELF.

L, White Russian general Anatoly Pepelyayev (Анатолий Николаевич Пепеляев, 1891-1938) led Siberian White Russian armies. He wanted to turn Russia into a democracy, and was executed in Josef Stalin’s Great Purges.

Throngs of refugees were crammed within a short distance of the US freighter, and word got out: Here was a way out of this hellhole. Among the displaced was wealthy Russian businessman Vladimir Petrovich, who’d bought the fuel oil. He was with his wife, two daughters, his Chinese associate Low Wong, Mrs. Wong and their son On. After a standoff between gun-totin’ revolutionaries and US Marines from Brooklyn, Ida’s officers, the Petrovich and Low families and others climbed or snuck onto the steamer.

Brooklyn’s captain gave Magee’s crew use of the big warship’s powerful radio and fully-equipped machine shop. The freighter’s engineer made up a new part for the drivetrain, and the ol’ rustbucket steamed hastily south to Hong Kong, not lingering to stock up on vodka or matryoshka dolls.

In HK, most of Ida’s refugees disembarked. The Mitsui shipping company arranged for some of the displaced persons, and others simply vanished.

The Petrovich family wanted to carry on to Singapore, where they were friendly with the Sultan of Johore. The two rich Russian girls had loaded up on clothes. In exchange for using Quinby’s cabin for his daughters, Mr. Petrovich handed the low-income radio guy a hundred dollar bill (remember his monthly salary was thirty clams.) On top of the cash, there were gifts of a box of Manila cigars, a silk Chinese robe and splendid chest, selected by Petrovich’s wife, made of camphor wood.

It wasn’t just the bling that impressed Jay though. Sonya Petrovich was beautiful, charming and a piano player skilled at both classical and gypsy music. Sonya spoke no English, but the two managed to get the point of mutual interest across. On the sultan’s vast estate near Singapore, the Yankee boy and Russky girl shared a luxurious howdah, a tiny compartment on an elephant’s back.

The radio operator told wealthy Mr. Petrovich he had an offer of a good-paying job at the new RCA trans-Atlantic radio facility in New Brunswick, NJ. Papa Petrovich, “the old Russian bear…[with] those bushy black whiskers and his burning black eyes” gave his blessing for the young couple to marry.

Ida made the short trip to Kuching, Borneo, where Quinby invested $2.75 to buy a pair of monkeys. He named the primates, who share 98% of our DNA or something, right?, Mike and Maggie. M&M provided tremendous entertainment for the crew, and a lot of exasperation for Jay. One observation that the radioman offers is deep and profound:

Retrieving a money from a ship’s rigging is a futile task.

The tramp steamer took on a load of mahogany in the Philippines, loaded up with coal in Myike, Japan, and started the long trans-Pacific journey back to San Francisco.